The Azerbaijani laundromat: a new money laundering machine in a familiar guise

Publication date 24-04-2019

D. Crijns, AMLC senior advisor

Most of you are familiar to the so-called Russian laundromat, a $20 billion money laundering scheme during the period 2010 - 2014. A few weeks ago, the journalist collective OCCRP published a new, similar scheme: the Azerbaijani laundromat.

In this article I will discuss four items. First the new scheme in short. Then I will deal with a special legal entity that is often used in this type of money laundering scheme, and give some examples and more detailed information. In the third paragraph I will focus on the role of the banks in the scheme and how the money actually got into the hands of the criminals. Finally, I will give examples of how the money is spent.

1.1 The scheme in short

The new scheme that came to light is referred to as the Azerbaijani laundromat. Our initial analysis on the basis of several publications[1] (including 16,940 transactions) and other sources gives the following picture. Via a large number of obscure transactions that appear to be linked indirectly to (influential) persons in Azerbaijan, an amount of almost $3 billion ended up with 4 companies under Scottish law via a network of companies. This money, which was lent by a bank, could not be repaid because due to this obscure structure the legal entities/persons who borrowed it, could not be traced when the money was claimed.

These 4 companies made substantial payments, again via a multitude of intermediary companies, after which large private purchases were made or assets were set aside on behalf of influential persons linked to Azerbaijan. In addition, payments were made that can be related to corruption.

In a word, a familiar money laundering structure in which money is withdrawn from authorities/businesses for unclear reasons, after which the money ends up with the central companies via obscured transactions (we often refer to these companies as hourglass companies). These hourglass companies subsequently set aside the money on behalf of private expenses or other payments (e.g. corruption/bribery).

1.2 What information do we have

These transactions took place in the period 2012 – 2014, almost simultaneously with the Russian laundromat. Fortunately, unlike previous money laundering schemes the journalist collective OCCRP and the Danish newspaper Berlingske published a lot of detailed information. The journalists obtained the details via a leak. The AMLC has analysed this information, also on behalf of other partners. As already mentioned, it involves almost 17,000 transaction details and more than $6 billion in flown assets. They used 350 different legal entities to pay and 1914 legal entities/persons who ultimately received money. In short, a large quantity of information that may not yet clarify all the details and of which we can conclude that the data appears to contain mistakes at detail level. But it does support the theory that money is being laundered here.

1.3 How did it work

Despite the fact that it is not entirely clear how exactly the money comes in, it does seem likely that almost half ($1,452,918,429 in 530 transactions in 2013 and 2014) was transferred via the IBA (International Bank of Azerbaijan) by a shell company linked to the Aliyev family (the president of Azerbaijan) and other local rulers. The name of this company Baktelekom MMC strongly resembles that of the telecom company BakteleCom, but it is an entirely different company and appears to be established in an ordinary apartment in the capital of Azerbaijan, Baku. Where the company got the money from, is not entirely clear (see below “Role of the IBA”). The other big funders (including Faberlex LP and Jetfield Networks Ltd) can also be linked to senior government officials, or carry out orders for the Azerbaijan government. In addition to this income almost $8.5 million comes directly from government organisations such as the Ministries of Defence, State security etc. However, there is also $29 million from the company Rosoboronexport (a Russian state-owned arms exporter).

After the money has been received it passes through various other companies, of which 33 (according to the OCCRP) also occur in the Russian laundromat, to 4 hourglass companies. From there, the money is redistributed again (see paragraph 4.1. et seq., Spending of the money).

2.1 The role of (Scottish) Limited Liability Partnership

Before we continue with the spending of the money, it is useful to have a brief look at a legal entity used within the scheme, namely the Limited Liability Partnership (LLPs, also referred to as Scottish LPs).

Of the 4 (hourglass) legal entities, 3 are Limited Liability Partnerships. In this case the LLP/SLP (hereinafter jointly called: LPs) is a legal form under English/Scottish law, but it also occurs in other countries.

LPs are legal forms that for a part can be compared with the Dutch ‘CV’, ‘VOF’ or ‘maatschap’. They are fiscally transparent, i.e. not the company but the owner is liable to pay tax. In the case of LPs there is a limited liability, but they can be independent legal owners of objects or enter into agreements.

LPs are used more and more often. For instance, between 2006 and 2016 there was a tenfold increase of these legal entities. But they also appear to be playing an increasingly important role in money laundering / concealment schemes, among other things because of this special combination of transparency of taxation, ownership etc. By contrast, in the end they are not very transparent because the actual ownership can be concealed. A good indication for the importance of this legal form for money laundering purposes is the fact that it is explicitly mentioned as an essential legal entity in the TV series ‘Narcos’.

In the Azerbaijan case, two of the LPs (Hilux services and Polux Management) are owned by Mr Ahmadov,[3] a taxi driver from a suburb of Baku. By the way, this person also owns the above-mentioned company Faberlex that takes care of a part of the funding.

In addition, the parent companies of the third hourglass LP (Metastar LLP) appear to originate in Belize and also appear to have a relationship with a large part of the new LPs that were incorporated the past few years. These LPs also include Armut Services LLP, a company that played a role in a previous money laundering case from 2008[4]. Our analysis shows that at least 75% of the amounts within the scheme went via LPs.

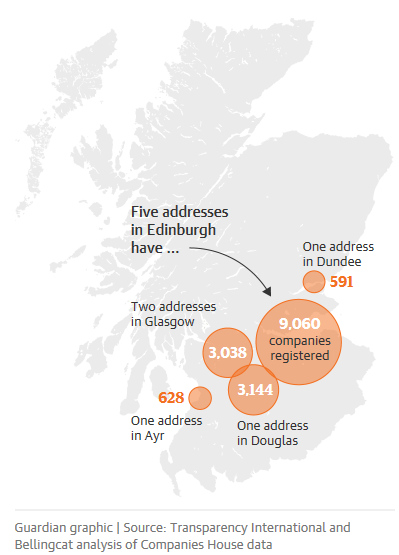

With regard to the LPs it is also notable that 70% of the new LPs incorporated in the past 10 years are registered at only 10 addresses. The address where Polux and Hilux are registered, is also the address of almost 800 other legal entities. By the way, it became compulsory in 2017 for the owners of the LPs to be transparent. The AMLC has had regular contacts with the British colleagues the past year about the use of LPs in possibly suspicious situations. So, if you come across this legal form in situations that may be related to money laundering, it can be useful to contact us.

2.2 The companies’ role in bribery

A specific example of the actual use of the legal entities we know now, is that according to an Italian investigation into bribery/bribes the above-mentioned companies Faberlex and Jetfield Networks (that were owned by our taxi driver) were used by Elkhan Suleymanov (Azerbaijan parliamentarian and member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) to pay the Italian parliamentarian Luca Volonte. Recently, the Dutch parliamentarian Pieter Omtzigt also clearly expressed his views on this and it became clear that probably more members of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe may be involved in this[5].

3.1 The role of the International Bank of Azerbaijan (IBA)

As indicated above, the IBA played a crucial role in the matter. In 2015 it emerged that this bank had provided loans at a very large scale the previous years; to business people but also to offshore companies. These loans appeared to be largely worthless, because they were not or could not be repaid, as especially the offshore companies were unknown. The bank’s CEO is currently in prison and the damage appears to be at least $1 billion. But I doubt if this is everything. Certainly if you know that at the beginning of this year the IBA tried to protect itself against its large creditors such as Cargill (large international trading company), Credit Suisse (bank), but also SOFAZ (the state-owned oil company of Azerbaijan) in court cases in the UK and the USA. The IBA’s debt is allegedly $3.3 billion. In order to rescue the bank more than ¾ has now ended up in in state hands.

Partly because of this pattern of providing large loans to offshore companies it could very well be that Baktelekom MMC received its funds from an IBA loan.

3.2 The role of the Danske bank in Latvia

It emerges from details of the Russian laundromat that many of the companies that play a role in the flow of funds have a bank account with the Danske bank in Latvia. Also in this case it appears that the companies involved hold bank accounts with this bank in Latvia. As a result of signals in previous money laundering cases, the bank indicated in the past that it only belatedly recognised the signals. The head of the bank’s legal department stated that they have taken measures, but that they cannot give any guarantees for the future.

4.1 Spending of the money

In the meantime a large number of spending examples have become known in more than 80 countries (Turkey comes a close second behind the UK). Within this scope a number of Dutch companies also emerge, but it is still unclear whether these companies played a role in the money laundering or whether they were only used or misused, or whether only regular purchases were made. In conjunction with schemes similar to the Azerbaijan case, consultations are taking place with other countries about the question if and how such cases should be dealt with in the Netherlands or in a wider context. In the UK, but also in the European Parliament[6] questions about the involvement of the UK and EU member states have already been asked or are being prepared.

Should you recognise a possible signal, please inform the AMLC. Europol has kindly offered to help in the exchange of information which is relevant for all member states involved.

The examples of the use are varied in nature. As already indicated there is a role with the bribery of one (or more) parliamentarian(s), but there are also payments to a football club or purchases of expensive private goods.

4.2 Payments on behalf of the Eyyobov family

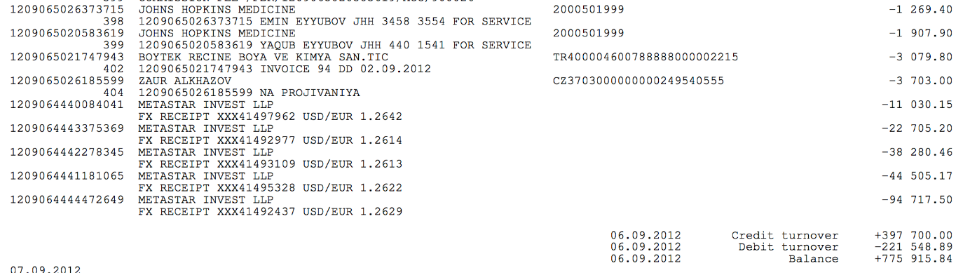

There are also bank statements from which it appears that medical expenses of a very important parliamentarian from Azerbaijan (Eyyobov) are paid via the central hourglass companies, either directly or indirectly via intermediary companies. In addition, his son is handed out millions. For instance, hourglass company Meta Star Invest LLP paid medical expenses directly (see example).

On being asked, Eyyobov indicated that Meta Star provided “Concierge services” and that disclosing these details is an attempt to put pressure on the regime.

In addition, there allegedly have been 27 transactions in which $9 million went to Velasco International Inc. (BVI company). Publications from several countries from the so-called Panama Papers (Mossack & Fonseca documents) provide indications that family members of Eyyobov are behind this company. Velasco Inc. owns immovable property and during a visit by a journalist to 2 apartments of the company in Baku it was allegedly mentioned that the son Yaqub Eyyubov is the owner.

4.3 Other payments

A large number of companies who received money were recently disclosed as well. Considering all the previous remarks and the documents published about possible money laundering and corruption this information seems to be useful on behalf of a further analysis. For this reason the AMLC is considering whether it can record this information in a transparent way for further data analysis, possible in cooperation with other countries.

Finally, I would like to reflect on an example of an entirely different kind of payment. A part of the payments is made to large well-known companies. For instance, in 4 transactions an amount of $5,521,514 is transferred to Ericsson AB. In this case it actually seems to involve the large telecom company and the descriptions of the payments refer to invoice numbers. At a first glance they appear to be regular payments. However, according to Ericsson there is no business relationship with the company that made the payment, in this case the 4th hourglass company LCM Alliance. It is yet unclear how Ericsson dealt with this payment and whether and how the money was repaid. The AMLC knows from other investigations into Laundromat-like schemes that frequently payments are made to large international groups. These payments are usually not considered suspicious. At the moment we are working on a project to gain more insight into this kind of transactions, in cooperation with other countries.

Again I would like to ask you to inform the AMLC if you come across a possible signal. Information which is relevant for all member states involved, can be exchanged with help from Europol.

5. Conclusion

In short, a new publication of a possible money laundering scheme. We hope that the information used for the reconstruction of the laundromat will help us to tackle money laundering, but also, and especially, to understand schemes.

Moreover, we must not forget to turn the available information into preventive measures in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing, so that we recognise not only special transactions such as (obscure) companies with bank accounts in other countries as risks, but also certain transactions which at first sight seem normal (what red flags do we see when we look back?). That way we are better able to understand the method of working behind apparently regular payments to companies such as the example of Ericsson, and to ensure that these companies can no longer be used in a money laundering scheme.

I hope that this article has given you some better insight into a number of important issues. Apart from the various published articles and their analyses, I have also used the AMLC’s general knowledge of money laundering.

This article is intended to increase the awareness and knowledge of money laundering and not to formulate suspicions. Proof of money laundering will be provided in a possible criminal case! But recognising and preventing money laundering, we do together.

If you wish to contact the AMLC as a result of this article please write to AML.Centre_Postbus@belastingdienst.nl.

[1] OCCRP and the Guardian

[3] Logically, Section 155 of the Companies Act 2006, from October 2008, “required that all UK private and limited companies must have at least one director that is a natural person” (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/46/section/155)

[4] Magnitsky/Red Notice case

[5] Algemeen Dagblad 19 September 2017

[6] https://www.occrp.org/en/azerbaijanilaundromat/eu-parliament-demands-investigation-into-azerbaijani-laundromat-revelations