The need for cash in labour-intensive sectors: the Cash Compensation Model

Publication date 17-02-2025

By: FIOD Intelligence Noordwest

Various analyses of unusual transactions by FIU-the Netherlands in cooperation with banks show that businesses have compelling reasons for needing cash.

Simple cash withdrawals may be undesirable if those reasons do not stand up to scrutiny. Such withdrawals can lead to unwanted enquiries from the bank, the accountant, the auditor, the tax authorities and, ultimately, investigative agencies. After all, cash is known to pose a risk of money laundering but is also often associated with other illegal uses such as paying staff cash-in-hand, making purchases off the books, paying bribes, profit skimming or disguising private expenses as business expenditure.

In the past, companies had their own cash pool for operational purposes. Since this cash pool is drying up as a result of electronic payments by clients, customers and buyers and banks focusing more sharply on cash transactions among their account holders, people are turning to another method: the Cash Compensation Model (CCM)[footnote1].

The entrepreneur uses this method to ‘buy’ cash from criminals. Those criminals may be individuals or criminal organisations. Cash obtained through the CCM is mainly used for illegal purposes. Cash-in-hand wage payments are a common example of this. The CCM is increasingly blurring the line between the underworld and legitimate business. That explains the current focus on this issue.

How does the CCM work?

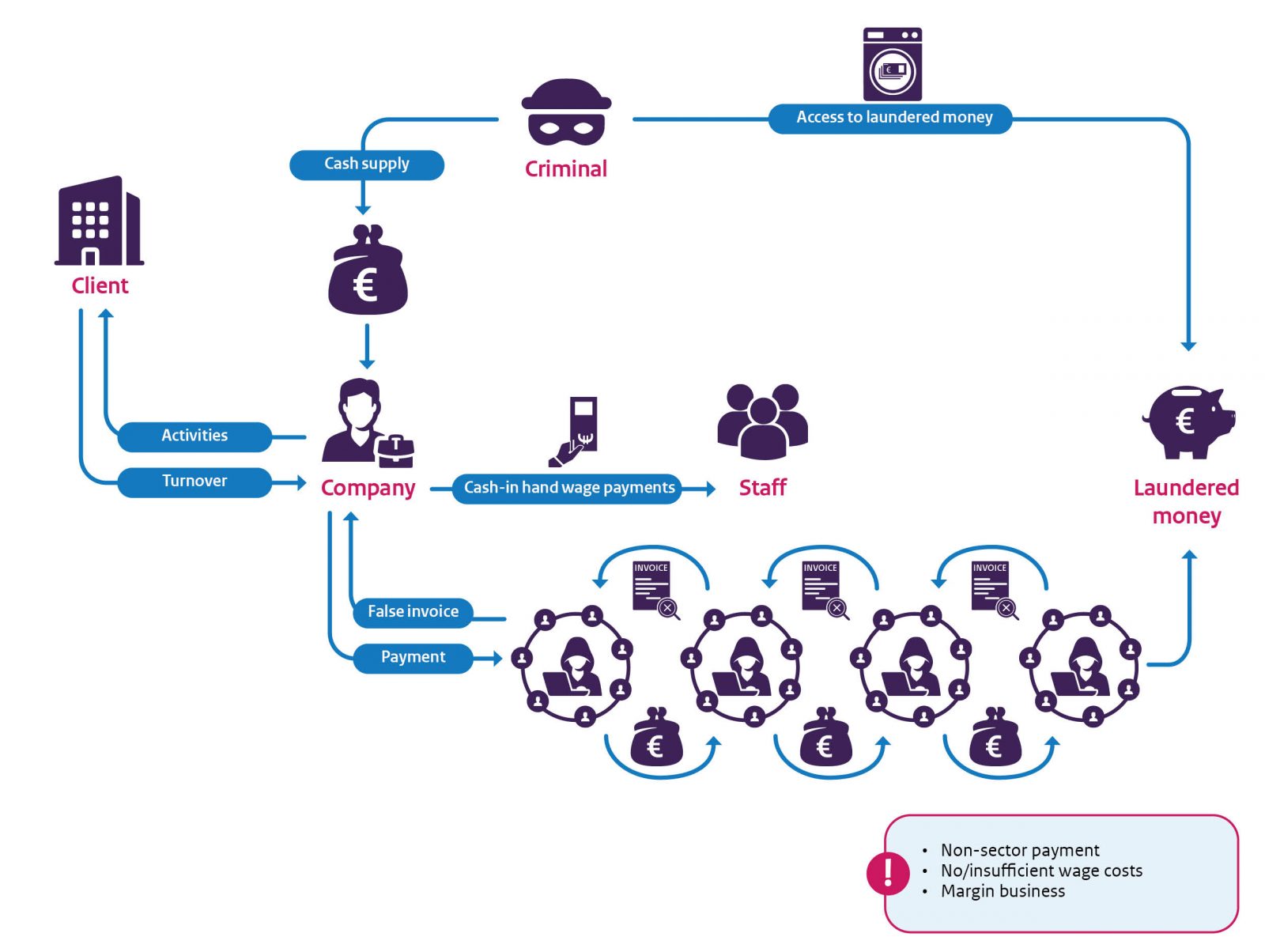

The CCM involves providing cash of a criminal origin to entrepreneurs who need it. The entrepreneur receives the cash but has a repayment obligation to the lender. A fake invoice is issued for "services rendered" or "goods delivered". The entrepreneur pays this fake invoice through the bank, and the invoice and payment are processed in the accounts. The cash flow (counter value) is kept off the books, and this is covered by the fake purchase/cost invoice. The entrepreneur can use the cash as desired, usually for illegal purposes. This conduct can constitute a wide range of criminal offences such as incorrect tax returns, forgery, the preparation of erroneous financial statements, corruption (in the public or private sector), and money laundering. The criminal lender gains by converting the criminal cash into cashless money and legitimising it with a fake invoice.

Tax motives and derisking

Banking supervision and customer due diligence by banks make it difficult for account holders to withdraw large sums of cash, systematically or incidentally, undetected. Financial institutions report unusual transactions to FIU-the Netherlands under the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Prevention) Act (Wwft). If there is sufficient cause, these transactions are flagged as suspicious transactions and referred to investigative agencies. Criminals set out to avoid attention in that area, especially if the withdrawn funds are used for illicit payments. Cash-in-hand wage payments, however, require a consistent cash pool. Enhanced supervision has not eliminated that need, which has led to new methods of obtaining cash, such as the CCM.

In practice

The CCM comes in many different forms. What links them is the criminal origin of cash and its use for illicit payments. One of the recognised forms is found in the subcontractor model.

The subcontractor model

Subcontracting is when a person or company commits to perform part of the work contracted by the main contractor. The main contractor receives funds from a (usually satisfied) client and pays the subcontractor the agreed fee. In this model, the subcontractor structure is abused to mask illicit payments and lend legitimacy to non-cash compensation payments.

An example

A company in a labour-intensive sector[footnote2] pays its personnel in cash and off the books. The cash used for this purpose is supplied by a criminal party that has obtained it from crime. The company must, of course, pay the criminal party for the cash obtained. For this purpose, a fake construction is set up involving costs not actually incurred but which are plausible as regards the company. The company used in this example operates in a labour-intensive sector, which means that transactions are ideally masked by using non-existent personnel costs. Cash-in-hand payments distort the turnover to personnel cost ratios, which can be brought back into proportion with this fake construction.

Here, the entrepreneur hires staff on paper for which a fake invoice is received. That fake invoice is paid by bank transfer. The employment agency sending the fake invoice is a link in a preplanned concealment chain. This chain consists of several Dutch and foreign employment agencies. In reality, the employment agency does not supply any staff at all, as the entrepreneurs already had staff that were paid cash-in-hand. To stay under the radar, the agency hires staff from the next agency in the concealment chain. Establishing that no staff were in fact placed with the entrepreneur, the second employment agency in the chain must now also be scrutinised. The chain is deliberately made long to ensure the success of the smokescreen formed by the concealment chain. A new employment agency appears with each successive fake hire in the chain, which makes it necessary to establish whether staff have been placed. Adding employment agencies outside the Netherlands to the concealment chain throws up barriers that make it harder to get to the truth.

The various employment agencies in the concealment chain send invoices to the previous link for fake hiring. The successive payments ensure that the funds paid by the entrepreneur move further and further up the chain. When these funds arrive at the last link in the concealment chain, the cash balances can be used as the criminal sees fit. The funds can be transferred to bank accounts in the name of or under the control of the criminal, but there are almost endless options that can also be considered. Take, for example, the purchase of real estate, luxury goods, investments in bona fide or non-bona fide companies, the purchase of fast speedboats (for smuggling), etc.

In the straight application of this subcontractor model, the last link in the concealment chain is, as it were, the criminal's money stash (the laundered money). The funds accumulated in it are used as desired. This can be shown in a stylised representation as follows.

Image: The CBS estimated the size of the annual black economy at around 4 billion in 2019 using figures from 2018. At that time, the two largest sectors were cleaning (€1.44 billion) and construction (€800 million).

Red flags

In a bona fide chain of employment agencies, the last link in the chain would have staff who were actually placed and for whom the agency also incurred the costs. This is where labour costs and remittances of taxes and social insurance contributions should arise.

In the case of the fake construction with a prearranged concealment chain referred to here, those labour costs are not paid. The last link of this chain includes payments that are not suited for an employment agency. These 'non-sector' payments are a red flag for the CCM. The absence of sufficient wage tax and/or sales tax payments by the company and the employment agencies also indicates that the CCM is at work. The successive hiring of staff, creating a kind of margin business for hiring and forward placement can also be cautiously seen as a sign of the CCM.

Professionalisation

It is clear that the CCM provides criminals with a revenue model for using cash. However, setting up good and reliable concealment structures takes a lot of time, knowledge, and skill. Viewed in that light, it makes sense to use facilitators. Considering all the knowledge of money laundering and professionally facilitating cash independently of time and place, it is hardly surprising that underground banking organisations are found here. There is no longer any need for a personal connection between a criminal and an entrepreneur needing cash. Therefore, this professionalisation in providing criminal cash is regarded as a particularly concerning development that calls for extra vigilance.

You only start seeing it once you know it’s there

Evidence of CCM is found in an increasing number of cases, and the information emerging from the interventions helps identify and combat this form of money laundering. That underlines the importance of recognising the signs.

Footnotes

[Footnote1, return to text] The Cash Compensation Model (CCM) is the name of a money laundering methodology "discovered" in the collaboration between the Serious Crime Taskforce (SCTF) and the Fintell Alliance. The SCTF is a public-private partnership with a focus on tackling serious organised crime and includes: the PPS, the police, FIOD, FIU-NL and six banks. See, among others, Government Gazette number 20390 dated 21 July 2023. The Fintell Alliance is a collaboration between FIU-the Netherlands and ABN AMRO Bank, ING, Rabobank, De Volksbank and Triodos Bank.

[Footnote2, return to text] Examples include, for example, companies in the cleaning, healthcare, construction, transport, parcel delivery, and telemarketing sectors, etc.